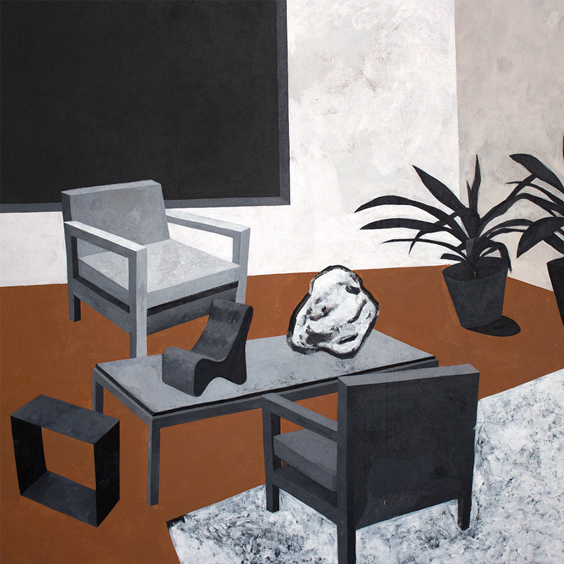

Rachel Shaw, All Seriousness, 2014. Acrylic on panel. Courtesy the artist and Galerie LOCK, Montreal.

Montreal based artist Rachel Shaw’s solo exhibition is currently on view at Galerie LOCK, showcasing her new series “All Seriousness”: a sequence of sterile, yet comically uplifting interiors. These waiting areas, offices, and living rooms have no visible entrance or exit; only black squares that lead to nowhere. Devoid of human presence, the furniture and objects no longer serve any utilitarian function and instead engage in aesthetic conversations with the viewers. The shadows, angles and intersections are only slightly off, lending to a peculiar unease on the part of the spectator. Caught in a state of in-betweenness, we can’t help but ask: where did everybody go? Shaw discusses her work with Jessica Kirsh.

Jessica Kirsh [JK]: There appears to be a reoccurring trope in your body of work: that of the window or frame. Most often illustrated as a black rectangle, it holds a stark yet mysterious presence within the interior. What signification (conceptually or formally) does this device contain? How is it repurposed or reconfigured from one painting to the next?

Rachel Shaw [RS]: In the diorama – a small-scale model of a real-life scene – a window (or at least the absence of a wall) is often as a point of view or observation. Even the word diorama means ‘through that which is seen’, which I think is pretty appropriate. I don’t use the word diorama to mean scale modeling or miniaturism, but I do use the window as a way to display a certain type of space while also containing it and the objects within it indefinitely. Formally, I think it works as a point of pause and reorientation, like a wall does in a maze, but it does hint at a space outside the one you’re in.

JK: You mentioned to me that this series represents a self-critique of your former work, commenting on its “comically self-limiting” nature. How did you try to visually convey this shift?

RS: Well, these are the products of self-criticism and effacement, but also responses to criticism I had received over the years – the colors I used were soft or feminine, the paintings’ smallness was cute or diminutive, the scale necessarily made them trivial, the flatness or darkness was obstructive, the “opaque” was a quality of my own thinking or speaking, and so on. It seemed to me that everybody thought I was so serious about this, which is kind of a classic, cartoonish assessment of a painter, but I also felt a little bit offended – like it all amounted to stubbornness, which is such a silly, petty and female trait.

On the other hand, I have made it ‘difficult’ for myself, and maybe even a little self-limiting – I insist on doing things the way I want to do them, even if that’s labor-intensive, and definitely want to have ‘my way’. I use small brushes and layers and layers of thinned-out, chalk-spiked paint to get the look I like, and I make a ton of discriminating little changes. Nothing I’ve ever done has ever been called ‘painterly’, which is still a term used to denote great worth. So with this series, I rendered things more starkly in black and white, I used bolder, more condensed colors in other areas, I made things bigger and flatter than ever, I let the viewer in from the other side of the window. Like, yeah, I’m kind of being stubborn and “whatever, man” about it, but ultimately trying to use that criticism for what it is.

JK: The technical calculations undertaken in the layout of your work – whether regarding the titled perspective, unknown light source, or disproportionate scale – effectively reject the precise mathematics inherent to illustration or design. This instead leaves room for a specific and personal curation of space – prescribed yet incongruous, controlled yet chaotic. Can you explain how your ideas are mapped out and translated into these imagined situations?

RS: I don’t start out with one finished drawing – more like a series of drawings and collages I can reconfigure, and it’s a constantly additive and subtractive process. I put in one thing and another thing, and then the floors, walls, ceilings and other things in response to those things. If I don’t like the way it looks, or it’s not getting the point across, I’ll move something over a little, change its color, cast it in silhouette or erase it altogether. Obviously I have some idea of what I want to do, but I don’t want it set in stone. I have a very hard time finishing anything.

Rachel Shaw, Recliner, 2014. Acrylic on panel. Courtesy the artist and Galerie LOCK, Montreal.

JK: The neutral color scheme and graphic composition in this series is quite industrial and Modernist; drawing links to the objects of Claes Oldenburg and the flatness of David Hockney’s paintings. From which source did you draw your inspiration for the design of these rooms?

RS: Furniture and interior design are huge interests, and I think that’s because A.) there are so many possibilities and configurations for a single space, so I could be interested in it more or less forever, and B.) the processes of collection / curation are really soothing to me. I’m a messy person who takes weeks to complete to-do lists, but my crayons when I was a kid (and my lipstick as an adult) were organized by brand, color, amounts left and then by preference within those categories. I tend to like Bauhaus stuff because it relies on the cube and the sphere, and those are such essential forms.

I do like David Hockney, but I feel like that’s the one cultural reference point I get and it kind of irritates me, because he’s more of a pop artist and so referential. Maybe it’s the same as being asked “So, who jumped in the pool?” I would say that A Bigger Splash made an impression on me – the stillness of the image, even in the movement of the water, and the water only hinting at a figure – but I’ve really always wanted to see the original photograph.

I do the blog thing, look at art, read books, watch movies and whatever, but the amount of time I spend on that isn’t as important as the amount of time I spend with my thoughts about it later.

JK: The absence of bodies in these interiors lends to a certain uncanniness; suggesting an inhabitable space or a void waiting to be filled by the spectator. The uneasy, psychiatric aura of these spaces reminds me of the anxiety associated with the waiting period before an appointment or meeting. Can you expand upon this “interpersonal conflict,” as you called it?

RS: Not to get weird, but the mind is a similarly uninhabitable space. My boyfriend has this saying, when one of us says something funny, that kind of annoys me, but also resonates with me – he says “the mind is its own place”. Some of these paintings are about things I’ve said or done, or that other people have said or done, and you could say that those are states of my mind. To be honest, these are the products of a period of disappointment and boredom for me – working too many hours, not painting as much as I want, having unproductive arguments, dealing with debt, immigration and other thought-suppressing shit. You want to see the light at the end of a tunnel, but you rarely get to go from point A to point B. There are periods of doubt, distraction, thoughtlessness and sadness that you might have to go through in the meantime, and for that, humor is a good shot in the arm. Further on the earlier point of self-criticism, I wanted to make my motivations more transparent to myself and others, and to consider my own presence and non-presence in my work.

Rachel Shaw, Tell Me How You Really Feel, 2014. Acrylic on panel. Courtesy the artist.

JK: The armchair in the piece Tell Me How You Really Feel seems to be making a certain gesture to the audience, as though animated with human-like emotion. Turned away and closed off in a corner, it avoids confrontation. Could you elaborate on the story behind this piece?

RS: Tell Me How You Really Feel is not about any one confrontation, but more about an attitude I thought I was indulging in a little too often. Being stubborn, petty and not a little bit irritable about it.

On the other hand, the objects on the table in All Seriousness are pencil sharpener shavings (mine) and a piece of gum (my boyfriend’s) that were on my nightstand for a really long time – I don’t necessarily want to betray my emotions, but that’s about personal space and a person, too.

JK: Materiality plays an integral role in your work, exemplified in the choice of wood panel as canvas, and in the addition of texture as a “punch line” (in your words). How much is your process directed by your choice of materials and your treatment of surface quality?

RS: The surface is important to me. I think that I like flatness because it’s so illusionistic. Sometimes I’ll see a painting online or in a book, and am disappointed when I see the real thing, because it takes up space and casts its own shadow and that kind of blows the whole thing for me. I’m not quite that anal, but I like the fact that a wood panel with a 2″ profile is such an object, and I like that this three-dimensional thing supports this two-dimensional interior.

Back to the term ‘painterly’ – as in using thicker paint with thicker brushstrokes, not following drawn lines. In contrast to that, the term ‘linear’ refers to the illusion of three-dimensionality, modeling the form through shading and more programmatic uses of color. I’m more interested in the latter term, but I don’t think I have the interest or discipline to produce really linear work. I don’t think I’m doing either thing – I mean, Botticelli is a linear painter – but what I am doing is trying to create an illusion of three dimensions while letting the entire painting create another, less specific effect. ◼︎

Rachel Shaw (b. 1986 Massatchusetts, USA) holds a BFA in Studio Art, Concordia University. She has exhibited both solo and group exhibitions at numbers of venues in Montréal including Galerie LOCK (2014, 2013); Parisian Laundry (2011); FOFA Gallery (2010); Les Territoires (2009) and Eastern Bloc (2009). Shaw lives and works in Montréal. rachelshaw.tumblr.com

Jessica Kirsh is a writer based in Montreal. She is currently completing her Master’s degree in art history at Concordia University.Her research is focused on new media, and issues of participation and spectatorship in interactive art. She has also been involved in gallery curation, both in Montreal and Toronto.

Rachel Shaw, All Seriousness, 2014. Exhibition View at Galerie LOCK, Montréal. Courtesy the artist and Galerie LOCK.

Rachel Shaw, All Seriousness, 2014. Exhibition View at Galerie LOCK, Montréal. Courtesy the artist and Galerie LOCK.

Rachel Shaw

All Seriousness

24 April – 03 May 2014

at Galerie LOCK

135 Avenue Van Horne, #203,

Montréal, Quebec, H2T 2J2,

Canada

galerielock.com

Opening hours:

Friday & Saturday 13h00 – 17h00

Follow Galerie Lock on Facebook