Myfanwy MacLeod, Everything Seems Empty Without You, 2009 & Hex (I–VII), 2010. Exhibition view. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada. Photo by M-KOS

With a second edition entitled “Builders“, the Canadian Biennial staged in Ottawa’s National Gallery an exhibition that perhaps went against the grain of mega international extravaganzas, and the usually vast array of ensuing curatorial ideas and ideals. This Biennale voluntarily took a hermetic and back-to-basics approach to its program, to exclusively centre on contemporary Canadian artists selected from the Gallery’s recent acquisitions over the past two years.

Curator Jonathan Shaughnessy cites in his catalogue essay that “Artists are builders in a rudimentary sense. They combine creative ideas, materials and technology with the aim to shape an original way of seeing and interpreting the world”. In an attempt to further canonize Canadiana, Shaughnessy’s title took inspirations from Toronto’s Hockey Hall of Fame, where Builders herein point to former players that go on to become coaches, managers or executives. Just as the hockey Builders were this way inducted for their contribution to the development of the nation’s most popular sport, Shaughnessy concludes that “In art, builders and players often prove to be one and the same.”

Fresh from the vaults of the National Gallery of Canada, a string works from emerging artists such as Melanie Authier and David Ross Harper mingle with others like Marcel Dzama and Ron Terada as well as veteran figures like Lynne Cohen and Michael Snow. This cross-generational survey of the nation’s talents comprises over 100 individual pieces by 45 artists, to embrace a multitude of disciplinary practices from all geographical backgrounds. Builders constitutes such a wide-encompassing show, that it at times risks a flattening of issues and subject matters. On the other hand, the works are so respectably themed from personal narrative to urbanization, the environment, identity politics, utopia and so on, that these read as a thorough cross-examination of Canada’s cultural material.

Evan Penny, Jim Revisited, 2011 ; Ron Terada, Jack, 2010. Exhibition view. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada. Photo by M-KOS

Large-scale sculptures draw our attention not only in their volume and scale but also for their show of craftsmanship: Evan Penny’s gigantic naked statue “Jim Revisited†(2011) introduce a figure and a plinth both slanting by some 20 to 30 degree, to depict visually anamorphic distortions on an otherwise ordinary man; Michel de Broin’s “Majestic” (2011) count as the biennial’s only outdoor sculpture, originally commissioned for the Prospect, New Orleans Biennial (2011–2012), to commemorate hurricane Katrina with displaced lampposts, and illuminate beacons of hope and resilience; David Altmejd’s “The Vessel” (2010) painstakingly assembled threads, plaster casts and other materials are confined in Plexiglas to tell a grand fairy tale of movement and metamorphosis.

At first glance summoning works by Donald Judd, the boxes lined with distilling objects in “Everything Seems Empty Without You†(2009) by Myfanwy MacLeod, contrast after scrutiny, with the pristine forms of Minimalism to reveal recycled wood and scrap metals. Alongside these are displayed colorful circular symbols entitled “Hex (I–VII)†(2010), which outline folk art shapes believed to ward off evil spirits. These also typify lowbrow genres, often disregarded in art institutions, to this way draw metaphors between the creatively refined and vulgar. Also mimicking modernist sculpture, Brian Jungen’s “Star/Pointro†(2011) ironically combines mass culture commodities and indigenous paraphernalia, to refute the threshold separating contemporary western and traditional First Nations aesthetics.

Sourcing personal anecdotes for inspiration, the “Object Waiting†photography series offer visual documents from Max Dean’s conversations with significant objects in his studio practice and personal life. Leslie Reid recalls distant memories to the canvas’ surface by overlapping both intimate and impersonal moments. Nunavut artist Elisapee Ishulutaq highlights, in graphite and oil sticks, sequences of her 80 year-long life on a massive nine meter long paper; with every painted stroke mindful of passing her heritage to future generations.

Jim Breukelman, Hot Properties 01, 1987/2008. C-print. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada

The critique of gentrification and homogenization in urban settings is a theme common to many lens-based artist within Builders. Toronto duo Young & Giroux investigate the trendy real-estate speculations of their city with their film “Every Building, or Site, that a Building Permit was issued for a New Building†(2008). At the antipodes of Young & Giroux hangs Jim Breukelman’s “Hot properties†(1987/2008/2011), a photo-series documenting small cottage-like houses in Vancouver, built over 65 years ago, each one adopting individual characteristics according to the different residents over the years. Away from urbanist issues, Sarah Ann Johnson travels north to explore a bittersweet odyssey in her latest series “Arctic Wonderland†(2010–2011). Here she not only captures the untamed beauty of nature but also the darker and alarming underbelly of man-made ravages, expressed via combining photography, painting and other media.

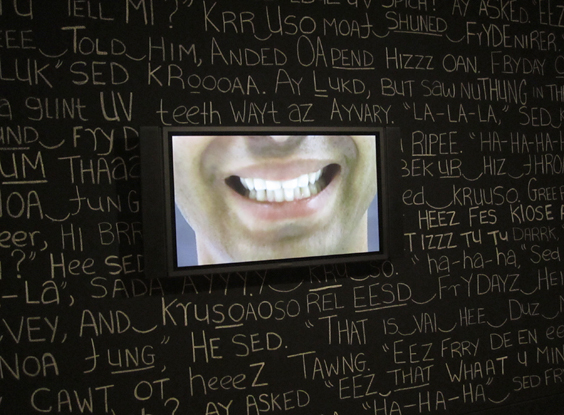

Titled similarly to J. M. Coetzee’s 1986 novel, “Foe†(2008), Brenden Fernandes produced a video self-portrait while taking language lessons of dialects from his own heritage (Kenya-India-Canada). Fernandes thus questions power relations between himself and his voice coach, reflecting on colonial histories that extend beyond modern capitalist landscapes. Vikky Alexander’s series of black and white photographs also evokes similar notions of failed utopia. Originally intending to scrutinize the Victorian iron and glass structure of Kew Garden in London, her focus shifted to the dense clustering of plants restrained in the architecture. Sympathetic to failed heavens, Terence Gower poses as a 1950s Walt-Disney-lookalike lecturer in “New Utopia†(2011) to analyze modernism and architecture, and propose uncanny examples from 1970s cinema such as: Parliament / Funkadelic’s 1974 Mothership Connection, The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, as alternative models.

Derek Sullivan, installation view, 2012. Courtesy national Gallery of Canada. Photo by M-KOS

The National Gallery significantly expanded its drawing collections over the years and included many such works in the Builders show. Among these we find Derek Sullivan pushing a poetic flavour of conceptual art. Devoid of any figurative element in his drawings, his choice of titles (“#25 Well hung Snow White Tan, Cadmium Light Red Purple, The Measure†(2007) and “#41 Vague, Mercurial Afternoon, The New Coterie†(2009)) does however allow a playful interaction between the shapes on paper and strikethrough description, to open up a multitude of individual interpretations and make his entire creative process a literal one.

Of the numerous artists here engaged in a continual cycle of critique, deconstruction and joining of traditions with contemporary life, the multidimensional aspect of this collection strikes one most clearly. Indeed the above works demonstrate how the National Gallery has built up an impressive collection, well worth the regular show-off. From a somewhat rocky start in the first edition, criticized two years ago mainly by Louise Déry, curator and the director of the Galerie de l’UQAM, for missing out on the opportunity for staging an international exchange, the Canadian Biennial seems now firmly aligning its mission with its national identity. If every future event continues to tap into the gallery’s recent acquisitions, surely the collecting process will fall in line with upcoming biennial themes, and embody two sides of a consistent enterprise. After all, Canada provides a very different arena than the usual market dominated art scenes of the world, and should be celebrated as such.

Melanie Authier, Augury, 2010, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada

Builders

the 2nd Canadian Biennial

2 November 2012 – 18 February 2013 (extended)

at National Gallery of Canada,

Ottawa

gallery.ca/builders

Curated by Jonathan Shaughnessy

Artists: Vikky Alexander, David Altmejd, Benoît Aquin, Melanie Authier, Jim Breukelman, Michel De Broin, Edward Burtynsky, Lynne Cohen, Chris Cran, Max Dean, Susan Dobson, Marcel Dzama, Brendan Fernandes, Robert Fones, Will Gorlitz, Terence Gower, David Ross Harper, Faye HeavyShield, Dil Hildebrand, David Hoffos, Simon Hughes, Elisapee Ishulutaq, Sarah Anne Johnson, Brian Jungen, Myfawny Macleod, Qavavau Manumie, Lynne Marsh, Scott McFarland, Jason McLean, Michael Merrill, David Merritt, Evan Penny, Sandy Plotnikoff, Jon Pylypchuk, Leslie Reid, David K. Ross, Mark Ruwedel, Michael Snow, Mark Soo, Derek Sullivan, Ron Terada, Joanne Tod, Steven Waddell, Daniel Young & Christian Giroux

Brian Jungen, Star/Pointro, 2011; Faye HeavyShield, body of land, 2002–ongoing. Exhibition view. Courtesy national Gallery of Canada. Photo by M-KOS

Brenden Fernandes, Foe, 2008. video installation. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada. Photo by M-KOS

Lynne Cohen, Untitled, 2007. Chromogenic print. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada.

One Reply to “Review: Builders, Canadian Biennial 2012 at National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa”