Can contemporary art in Japan transcend its Galápagos Syndrome

M-KOS sends sincere commiserations to all the people affected by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake.

<align=”justify”>

Tabaimo “teleco-soup” (2011) Installation view at Japanese Pavillion, the 54th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of the artist, Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo and James Cohan Gallery in New York

At the 54th Venice Biennale, the Japanese pavilion is presenting Tabaimo, a 36-years-old Japanese artist who’s work is renown for uncanny and hypnotic animations of manga and ‘anime’ inspired Ukiyo-esque imagery. Her installation entitled “teleco-soup†is a circular piece surrounding the viewer from floor to ceiling, with moving images of Japanese towns and flowing water. In its centre, the installation features a well-shaped circle also projected onto with similar animations. “teleco-soup†evokes an inside-out inversion between water and sky, fluid and container, self and the world, a term developed from the original concept of “Transcending Galápagos Syndrome†initiated by this year’s Japanese commissioner, Yuka Uematsu. Tabaimo refers further to the proverb “A frog in a well cannot conceive of the oceanâ€, attributed to Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi, and adds this to the Japanese expression “But it knows the height of the skyâ€, as a lateral way to speak about her work. The latter articulates an outward manifestation of Tabaimo’s introspective gaze, and by extension, reflects on Japan’s island state of mind, isolationist in nature, and its multiple-century era of seclusion from all foreign contacts*.

During its long period of isolation between the mid 17th to mid 19th Century, Japanese culture developed, flourished and established a distinct character in many different areas – Ukiyo-e, Haiku, Bunraku, Kabuki, and so on. When opening up her borders again, Japan became a source of inspiration for many westerners, as Japonism was highly influential in the advancement of European Impressionism, Art Nouveau and Cubism. In recent history, manga, anime, fashion and Haruki Murakami’s novels have widely spread around the world as Japanese contemporary cultural commodities.

But many success stories within the country’s confines travel less easily, in art or even industries like technology. For instance, domestic mobile telecommunications have developed to such an exponential level of innovation in the mid-2000’s, that their usage became impossible outside of Japan. Nomura Research Institute has coined this condition as “Galápagos Syndrome†to describe a phenomenon, product or society evolving in isolation from globalization. Japanese mobile phones cannot function outside the specific settings of their limited environment, just like the indigenous species Darwin encountered on the Galápagos Islands.

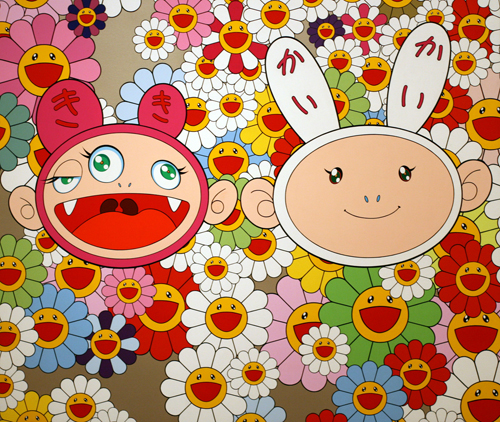

Takashi Murakami “Kaikai Kiki News” (2001) Courtesy of the artist; Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd and Gagosian Gallery

In today’s contemporary art world, Japan’s influence is undeterred. Takashi Murakami tops the list of most reputed international artists in Japan, his “Superflat†series pointing to various graphic forms of popular culture, such as manga and anime, J-pop as well as the shallow emptiness of Japanese consumerism. An entrepreneurial artist and powerful figure in the international art scene, Murakami was ranked 39th in Art Review’s 2010 survey for the most powerful figures in the contemporary art world. Yoshitomo Nara’s subverted cute images of children, deceptively innocent faces revealing aggressive and sinister undertones, also show clear influences from Manga and anime culture. In her early works, Mariko Mori paraded in costumes of sexy cyborgs, as if virtually popping out of mangas magically brought her to international acclaim. Inevitably the oversized eyes and hair-do’s of comic book characters and such likes, have become the stereotypical staples of Japanese contemporary works, especially of those viewed outside Japan.

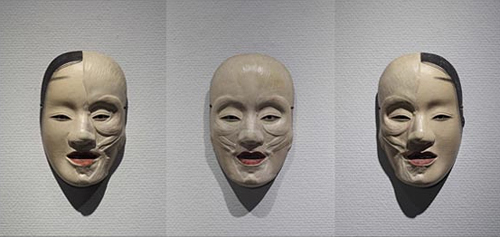

Motohiko Odani “SP Extra: Malformed Noh-Mask Series: San Yujo” (2008) wood, natural mineral pigment, Japanese lacquer, paulownia-wood box. Courtesy of Yamamoto Gendai

In March 2011, the Japan Society in New York held the exhibition “Bye Bye Kitty: Between Heaven and Hell in Contemporary Japanese Artâ€, a survey of Japanese contemporary art, curated by David Elliot. A long-time resident of Japan, Elliot gained a firm reputation as director of Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, between 2001 and 2006 . With “Bye Bye Kitty†he attempted to overthrow previous assumptions of “Cute†or “Otaku†in Nippon art, as established by “Little Boy: the Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subcultureâ€. This 2006 exhibition, also hosted by the Japan Society, was unsurprisingly curated and self-staged by Murakami himself, featuring similarly “Superflat†artists.

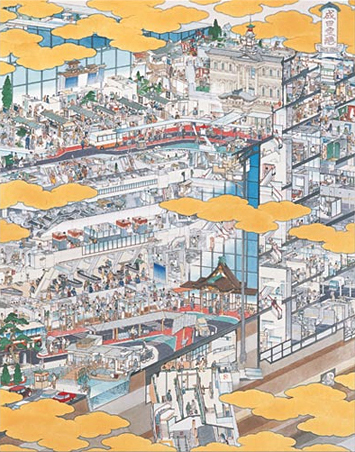

Elliot selected mid-career artists who, apart from Yoshitomo Nara (also in “Little Boyâ€), are lesser known outside of Japan and Asia. The exhibition included works from Makoto Aida, Manabu Ikeda, Tomoko Kashiki, Rinko Kawauchi, Haruka Kojin, Kumi Machida, Kohei Nawa, Motohiko Odani, Hiraki Sawa, Chiharu Shiota, Tomoko Shioyasu, Tenmyouya Hisashi, Akira Yamaguchi, Miwa Yanagi and Tomoko Yoneda. Conversely some of the works selected in Elliot’s program seemed to carry more traditional and other strongly recognizable legacies, such as Yamato-e, Nihonga or Noh masks updated with contemporary cultural references and very specific narratives. Rather than bring any resolve, this fact merely deepened the issue of Japan’s resort to self-caricature, in order to reach global attention. National cultural surveys such as the above, may get away with Japanisms, but we will unlikely see all the artists in “Bye Bye Kitty†fit into unprotected international contexts of commercial galleries, auctions and the like.

Akira Yamaguchi “Narita International Airport: View of Flourishing New South Wing” (2005) pen and watercolour on paper Courtesy of Mizuma Art Gallery. Private collection, New York © Akira Yamaguchi

Sociologist, Adrian Favell wrote in Art in America, March 2011,

“The fact is that, however brilliant contemporary art may be in Japan, it will go international only if there are cultural entrepreneurs who are smart and energetic enough to make it happen. This was Murakami’s great success, in alliance with his Western curators, dealers, collectors and fans. Back home in Japan, many people are tired of playing the global game. Murakami is famous there, yes; but he is neither loved nor much respected. Increasingly, the Japanese contemporary art world is content to simply talk to itself.â€

Favell’s statement singles out the “Galápagos Syndrome†with a sense of urgency. Indeed, there is no use in denying it, to embrace and go beyond this situation is at the core of the Japanese pavilion’s “Transcending Galápagos Syndrome†biennale theme. However, in the aftermath of the recent quake and nuclear threats, when many foreigners have moved away from Japan and the country faces a grave reality check, will such logic really ensue? These are the new challenges for contemporary art, as much as for the whole social fabric of Japan.

* During its isolation period, Japan closed its borders from all foreign contacts apart from trading with Korea, China, Ryukyu Kingdom (currently Okinawa) and the Dutch East India Company.

My Grandmothers/Geisha (Akiyo/Mai/Hitomi/Noriko) (2002) C-print, plexiglass, text panel. Courtesy of the artist

and Yoshiko Isahiki Office. ©Miwa Yanagi