Text by Joseph Henry

Exhibition view, ABC : MTL at Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2013. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

Montreal-based Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) has devoted roughly a year of programming (from November 2012 to March 2013) to an extensive curatorial investigation of the city’s cultural life and multi-faceted urban structure. With its three-part exhibition ABC : MTL, the CCA announced an open call for submissions, to nourish a diverse presentation of objects ranging from Robin Pindea Gould and Fiona Annis’ rigorous documentation of Montreal bridges to the architectural renderings of the Centre du Soccer, in the neighborhood of Saint-Michel. ABC : MTL additionally supplemented a smaller exhibition entitled Streetview, a collection of photographs spanning from the early twentieth century to present times, to offer portraits of the city via its canals, roadways and plazas.

In their curatorial statement for Streetview, Martien de Vletter, Louise Désy, and Mariana Siracusa claim: “There is no single image of Montréal. The city is constructed from a range of viewpoints captured from different perspectives. Streetview […] shows the quotidian experience of Montréal through the 20th century, as opposed to the cliché or ironic.†So do the curators articulate the myriad of perspectives offered in Streetview, which speak of the city’s everyday heterogeneity and fundamental diversity, resilient to any overarching or comprehensive representation. Melvin Charney’s poetic scenes of early industrialization as much as Alain Leloup’s lens-based investigation of St-Laurent Street laborers illustrate the topography of urban experience, to find numerous analogies in the diverse perspectives of Streetview’s photography exhibition. In the CCA’s optic, the Western, late capitalist metropolis is paradigmatically vigorous, a persistently accommodating repository of multifarious, fluid life.

Still, as offered in some works by Leloup’s 1980-1982 piece Boulevard Saint-Laurent, urban scenes of the everyday already testify to the operative structuring of civic authority. The seemingly utopian open-endedness of Montreal is characterized as an uneasy admixture of social, economic, and cultural power. Politics frame the street view, guiding one’s perception of the city and determining which spatial forms it might take. Although part of ABC : MTL, Montreal-born Vincent Chevalier obliquely responds to the Streetview exhibition with his 2013 photographic installation PWIF’d (“Places Where I’ve Fuck’dâ€), in setting up aesthetic and political coordinates where urban spaces ambiguously express the experiences of queer sexuality.

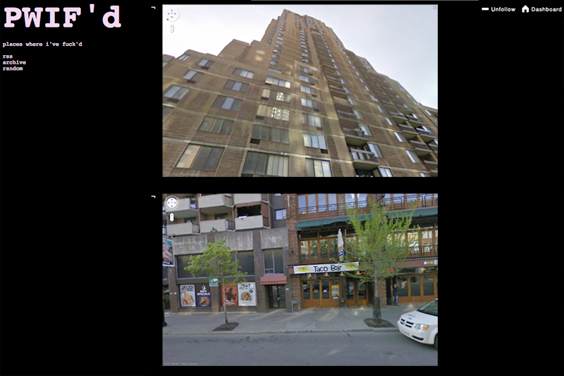

Vincent Chevalier, PWIF’d, 2013. Courtesy the artist

With PWIF’d, Chevalier organized a grid of screenshots from Google Street View (GSV), each image captioned with details of its location, the artist’s age at the time and the sex acts performed – the latter expressed in the cryptic shorthand of gay sex chat rooms (“#pnp,†“#w/sâ€). Ranging from banal to dramatic descriptions (from a normative standpoint), Chevalier’s photos chronicle some noticeably precocious adventures, while others acknowledge ostensibly ‘bizarre’ or ‘deviant’ erotic acts such as urination (“#pissplayâ€) or degradation (“#pigâ€). Every apartment building, parking lot and urban green space in PWIF’d assumes the generic format of the Google imaging tool, shot from the street and presented in a clear, square composition. The documentarian sensibility of PWIF’d takes on a severely clinical idiom, aiming for a maximum of information. The artist’s choice of GSV scenes at times resembles Streetview: a Montreal residence in Chevalier’s piece emerges as the digital equivalent of David Miller’s more stylish 1970s snapshots of city dwellings in the adjacent exhibition, each photograph offering a formalist depiction of urban architecture. Yet it’s precisely this avoidance of dramatization that places PWIF’d within the urban ordinary, championed by the CCA exhibition. The clear, cool visual treatment mitigates all the affective charge within Chevalier’s exploits.

If the depictions in Streetview were meant to represent each photographer’s distinct experience of the city and thus stand for a subjective instance of urban phenomenology, Chevalier opens up a discrepancy between his visual forms and their narrative content, i.e. the Google snapshots and the anecdotes of fucking. He colours the documentary quality of GSV with his coded sex acts, exemplifying what anthropologist James C. Scott has called “the hidden transcript†of marginalized or oppressed social groups. Queer space in PWIF’d is a partly visible space, not available at the level of indexicality but intimately saturating the image with supplementary captioning. Chevalier’s queer experience of the city doesn’t take on an expressive dimension like the artists in the Streetview exhibition: he operates by estrangement, perpetually identifying spaces which might suit his aims without directly disclosing its subtleties to the uninitiated. Not all street views accommodate the full range of urban life, especially those relating to practices considered non-normative, peripheral or even debased, such as online sex. When placed in dialogue with PWIF’d, the more celebratory pictures of Streetview now seem to address a decidedly more conventional or even privileged point of view.

Vincent Chevalier, PWIF’d, 2013. Courtesy the artist

That is not say that PWIF’d only concerns itself with the imagined titillation of anonymous sex. Chevalier’s use of automatic drive-by photos echoes earlier street images, much like those of André Blouin. The latter’s 1958 series Boulevard Dorchester from Streetview presents a similar road-bound imagery, visually organized along a horizontal axis and a vertical distribution of architectural planes. One triptych sequences the blurry image of a fence to convey a sense of motion that resonates with how GSV renders its bustling figures out of focus. Seemingly taken from his car or from the street-side pavement, Blouin’s work in Streetview is not so much about different locations in the city as it is about the differently moving patterns that inform and shape the said locations. Blouin and Chevalier’s projects might resemble Ed Ruscha’s 1966 Every Building on the Sunset Strip in which he sardonically documented a changing Los Angeles landscape in transit, then in the midst of a postwar econonomic boom. Blouin’s Rue Dorchester, dramatically widened and commercially developed three years prior to this photo, ambivalently follows similar lines. In one striking image, Blouin frames a large map of Montreal painted on the wall of a building. Shot from across the street, Blouin focuses on a city-dweller scanning the map – navigational skills must endlessly accommodate cities visibly scaling up to flows of capital.

Chevalier’s work focuses on the movements and mappings of queer sexuality through an urban environment rather than simply investigating the psychological narrative of each sexual encounter. The road-side photographs of Google or Blouin instead focus on the relational fabric of the city, its interconnectedness along lines of movement and transportation. In his somewhat romanticized essay on GSV, artist Jon Rafman is drawn to the format by its endless potentiality, to the way urban geographical proximity can stage an infinite range of affects and actions. In its ubiquitous, standardized documentation, GSV records an ostensibly limitless range of human experience, but unlike the assemblage of perspectives gathered in Streetview, the former subsumes them into a singular aesthetic. As urban places of sociality becomes hyper-legible and hyper-factual, turning the streets into a monitored and documented stage, the wall map in Rue Dorchester balloons in GSV, as a de facto image of Montreal.

André Blouin, photographer. Boulevard Dorchester, Montréal. 1958. Gelatin silver print, 19.3 x 24.1 cm. Fonds André Blouin, CCA Collection. ARCH264312 Gift of André Blouin

Chevalier comments on the risks of Street View’s “archival impulse†(quoting Hal Foster) and the way it saturates representation of the urban quotidian. In the already precarious sociality of queerness, private topographies and alternative publicities become crucial scenes. By de-literalizing a given homoerotic act yet recording its occurrence in the public sphere, Chevalier challenges the homogenizing gaze of GSV and its claim to transparency. During Chevalier’s artist talk organized at the CCA in March of this year, activist Ryan Conrad commented on the relationship that PWIF’d poses to increasingly privatized zones of queer communities, where open spaces of queer desire fall within the jurisdiction of corporate surveillance, à la Google. When public spheres get flattened (literally so under GSV aesthetics), alternatives are evacuated and queer spaces become monitored, recorded, and immediately marketed as such. The movement of queer bodies on the roads, alleys and pathways of urban living scapes become urgent sites of political negotiation, to navigate the border between private pleasure and public scrutiny. â–

Joseph Henry is Assistant Editor at ARTINFO Canada and writes freelance on contemporary art and politics. He’s published in venues such as The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Believer Logger, The New Inquiry, and esse, and worked at institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He lives and works in Montreal.

One Reply to “Essay: Sex in Public – Streetview and Vincent Chevalier’s PWIF’d at the Canadian Centre for Architecture”